The Azrieli Faculty of Medicine

The Burden

—and Comfort—of Proof

As the only expert in Israel on the human body from brain-to-toe, anatomist Dr. Alon Barash has worked every day since October 7th to identify the bodies of the murdered and the missing, and offer closure to their families.

Singular Expertise

As a child, Dr. Alon Barash of the Azrieli Faculty of Medicine wanted to study dinosaurs. When he discovered that there are no dinosaur bones in Israel, he switched to Neanderthals instead. “I always said, I want to do research that just plain interests me. I wasn’t worried about doing something that was seen as ‘important,’” he says. Yet after the Hamas massacre of October 7th, his unique—and uniquely comprehensive—knowledge of the human body nonetheless led to what he describes as “the most difficult and important service of my life.”

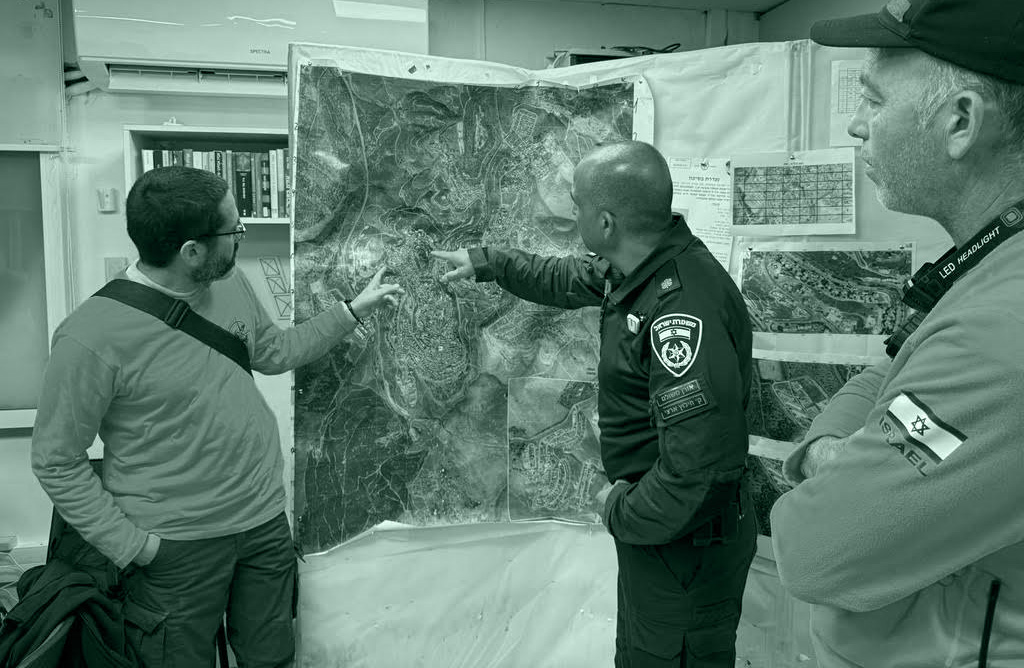

A physical anthropologist with expertise in human anatomy and skeletal biomechanics, Barash has long volunteered, alongside his research on early fossil hominins and teaching of anatomy, in assisting the IDF in investigating, searching for, and identifying missing soldiers. (“There are still 150 missing soldiers from the War of Independence, and we work to identify their remains every day,” Barash says.) He also helps the IDF in cases of mass fatalities, such as terror attacks that require the rapid identification of victims. “We owe it to the families to hear of their loved ones’ death from army representatives, not from the news or social media,” insists Barash.

Yet after the slaughter of October 7th, in which Hamas brutally murdered more than 1,200 Israelis, his expertise took on a heartbreaking urgency. Explaining that many of the bodies were so badly charred there was no way to extract DNA, Barash was called upon to identify dozens of victims by means of their skeletal remains. He also uses skeletal remains and bone fragments to determine if missing and kidnapped Israelis can be conclusively declared dead.

While he emphasizes that the work is conducted by a tireless “team of angels” from the Military Rabbinate and the IDF’s Missing Person’s Unit, he concedes that he is the only one in the Israeli army—and one of just two individuals in Israel—with the ability to determine a victim’s identity based on a part of his skeleton alone. The experience has driven home the need to train others for the task, which, he adds, requires not just scientific expertise, but the ability to manage large-scale recovery scenes. “Finding every last victim requires archaeology-like excavations, and we need to make sure no one’s remains are lost in the effort to find him,” he says. He also plans to publish research on his experience, in the hope of helping anatomists around the world to identify victims of attacks or disasters in extreme situations.

“This isn’t work that anyone would ever want to do, but when I look parents in the eye and tell them that I know, with complete certainty, that they can now begin grieving for their missing child, I understand that it is a gift of mercy, and I feel privileged to be able to give my people at least that.”

“Long after other reservists have gone home, my team and I will still be working. We’re committed to serving until every Israeli has come home, and every Israeli family has closure about the fate of its loved one.”